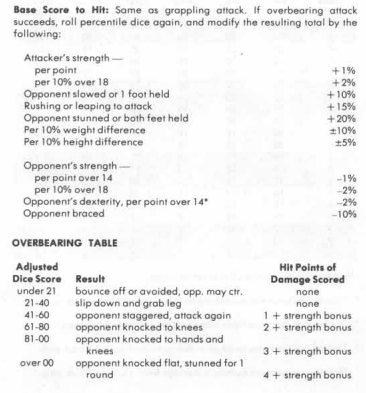

Overbearing in AD&D means an unarmed action where an attacker attempts to knock his opponent off his feet. The base chance of success is exactly the same as for grappling (discussed here and here). Where overbearing differs is in the effect.

The biggest difference is effect is modified by only the attacker’s strength, not the attacker’s strength and dexterity. The defender though still retains modifiers for both strength and dexterity.

But, you’ll note the header picture I chose is not of unarmed people engaged in martial arts. No. It shows ranks of spearmen beset by lance armed cavalry. What does that have to do with overbearing? It has to do with an overlooked (in RPGs) aspect of medieval warfare and how when you use all the rules of AD&D you get better results.

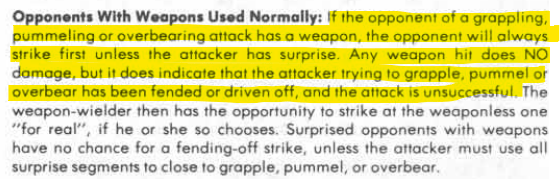

I’ve earlier discussed aspects of the spear. The spear has numerous advantages. The first being that it’s cheap. The second being that it’s effective. The spear’s effectiveness extends beyond its mere damage dice rolled. The spear is effective because it is longer than many other weapons. It’s this length results in it gaining the advantage of attacking first when charged. It’s effective in that it can also be braced against charges to do double damage. In addition, like all weapons, the spear can be used to fend off unarmed attacks.

As we saw when grappling large creatures, the weight of the overbearing creature adds a huge advantage when attempting to overbear an opponent. In my previous example, the ogre’s weight of 650 pounds pretty much completely wrecks even exceptional human sized opponents. Well, what of a horse? A smallish horse might weigh 900 pounds, and a large one a ton or more. I think we all know, how unwise it is to be in front of a stampeding horse. That charging cavalry is going to go through that line of foot infantry like it wasn’t there.

Except for the spears. The spears not only force cavalry to think hard about that double damage, but spears can be used to fend the horses away. It turns out horses don’t like to be poked with pointed sticks. In AD&D, if someone charges you with the intent to overbear, you can fend that horse away with your pointed stick. And because it’s a fending action you do that first. So, bye-bye cavalry. Sorted.

Not so fast. That’s where lances come in. The lance being carried on horseback can be both heavier and longer than a spear. So, per the rules, in a charge the longer weapon attacks first. The lance removes the spearmen, giving the horses the opportunity to plow through the line and overbear the footmen. In a sense, the lance was invented to remove the spear in order to allow the massive, well, mass of the horses to do their work of scattering the footmen like bowling pins. It’s an arms race of course. You can make the spears longer. Then the lances longer. Eventually, this ends up with the pike. The pike being impractical for much of anything except use in mass blocks and so long as to be a bother even on horseback.

Conversely, sport jousting always has a fence between the horses. This is to protect the riders, but also the horses, from collision. The fence helps prevent overbearing in a sport context, because it’s the overbearing that’s the most dangerous part. Two galloping thousand-pound beasts with a closing speed of fifty miles-per-hour is no joke.

As I’ve mentioned before, the Monster Manual was published prior to the Dungeon Masters Guide and therefore before promulgation of the unarmed combat rules. The Monster Manual does not have the unarmed combat statistics for horses (or any other monster). So, how do we go about using these overbearing attacks? Well, see below, I’ve provided some. And, not just for horses, either. Because footmen are pretty paltry targets for heroes. Real heroes go after dragons. The game is not named Dungeons and Peasant Levies. No, the game is Dungeons and Dragons.

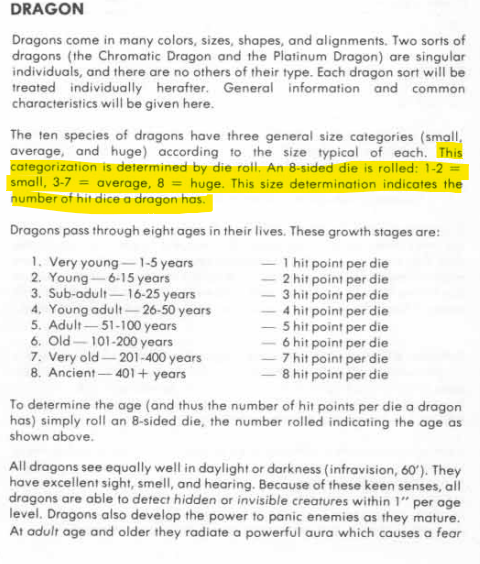

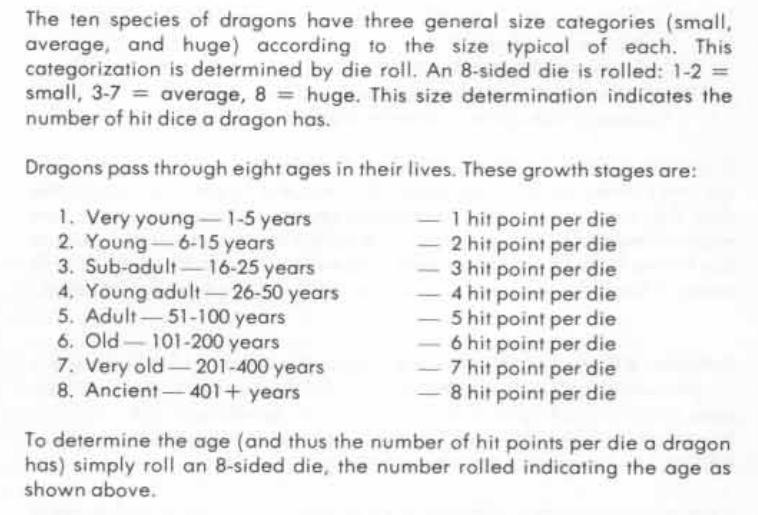

Now, I know what you’ll say. Like the Roc example from my previous post, dragons are huge. A horse can’t overbear a dragon. I beg to differ, it depends on the dragon, and the age of the dragon.

Dragons can be very young, or ancient; small to huge. Plus, dragons can be subdued and ridden themselves. So, wouldn’t we want overbearing rules for dragons too?

A few preliminaries. Both horses and dragons get melee attacks. Those do not use the unarmed rules, and can be used as fending devices too. Horses hooves are weapons unto themselves, so, no pummeling for these beasts. How about grappling. Horses have no hands, so grappling is out for horses, leaving horses with just overbearing as a tool. Dragons, subject to referee judgment, may be allowed grapples. Dragon claws are probably dextrous enough to grab things, and their tails possibly as well.

It’s interesting to note that later editions of D&D added a whole slew of dragon body part attacks wing buffets, tail swings, etc. and people thought that was a pretty cool thing and remarked that it really spiced things up from the “simpler” AD&D dragons. But, such attacks were there all along. What is a “wing-buffet” but pummeling? What is a tail sweep but overbearing? What is being grabbed and carried off in a dragon’s claws but grappling? One just has to do the work of following the rules. And, use one’s imagination to determine the unarmed combat ability statistics for dragons (or other creatures.

For horses, I’d forgotten. I already addressed their overbearing properties here. But I’ve updated my table a bit to add in the modifier of the unarmed variable based on the column of their attack table.

The rule for the variable says to used the number of the column in the attack matrix that is used. Horses use the monster attack matrix table. There is something to remark here. Similar to how fighters get a small advantage over other classes because their table includes the zero level column that other classes don’t, the monster attack matrix includes several columns less than one hit die creatures and also columns for 1+ hit die creatures. What that adds up to is a two hit die horse gets a +5 to their variable die, whereas a two hit die fighter gets a mere +2 and a two hit die magic user a measly +1. How to explain it? Well, the easiest thing is to assume monsters and animals are just naturally fiercer than people. But look at the table. That two hit die creature only needs a 6 to hit AC10, whereas a fighter needs to be fifth level to equal that. And, if you look at the column for a fifth level fighter, that’s the fourth column, the fifth level fighter would also get a +4 to his variable. This is just another example of how the diverse systems within AD&D have an amazing level of internal consistency.

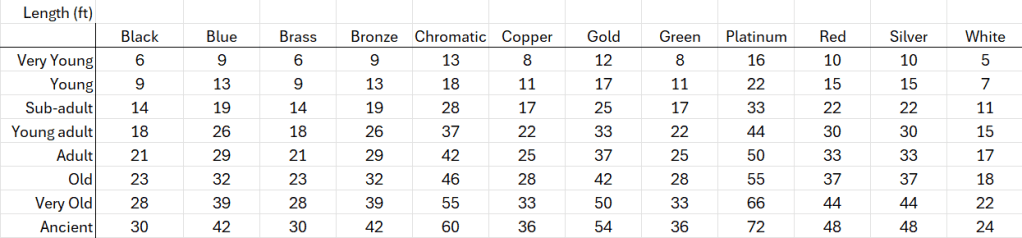

For dragons, it’s a little tricky. Dragons have eight age categories and three size categories that do not match up with the other monster size categories. Only one length is given for each dragon type.

For example, here we see a black dragon is large and 30 feet long. But what age does that correspond to? Who knows? For my purposes I chose that to be the size at maximum growth and then scaled that down for the age categories.

I’m choosing to use length as analogous to height for dragons. This is because they are sinuous and have snake-like characteristics. You might choose another variable like height at the shoulder or something like I did for horses. It’s a judgment call for how you want your dragons to behave. Below are the length values in inches.

For weights, I choose weights on the lighter side. These are flying creatures, after all. I based them in light aircraft weights of similar length. Ridiculous, true. But one has to start somewhere. Then I extrapolated back to the younger stages using an exponential function. Given the age categories are the same for all dragons, these assumptions meant that the largest dragons needed to start out smaller, given the larger weight gain with age. There are any number of ways you could choose and starting weights. I kind of like this, as the dragons with the most potential nonetheless start out weaker in a way. This is also roughly in the order of how common a dragon type is. The more common dragons start out bigger and thus more likely to survive their youth.

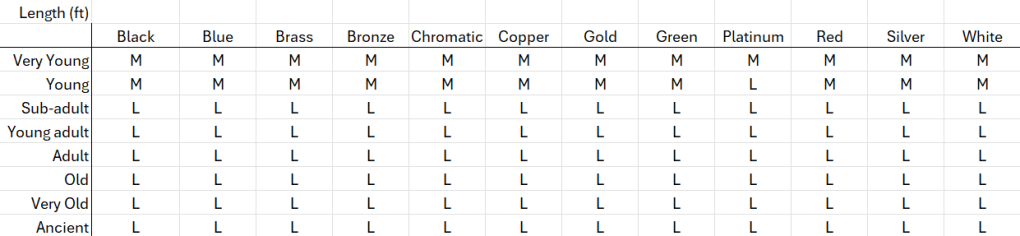

For standard size classification (for melee weapon damage), most of the dragons are large as listed in the monster manual. But for younger dragons I reclassified most to medium size.

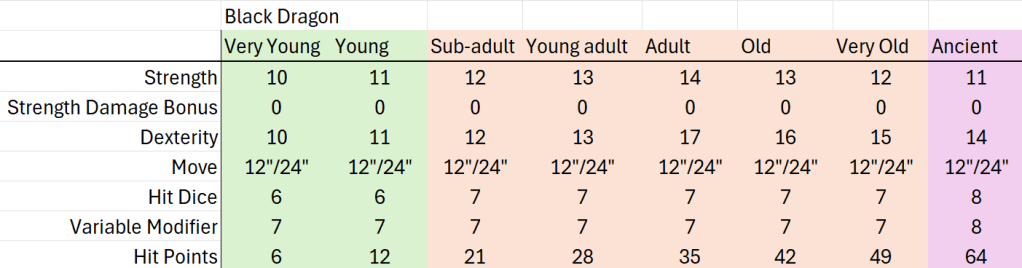

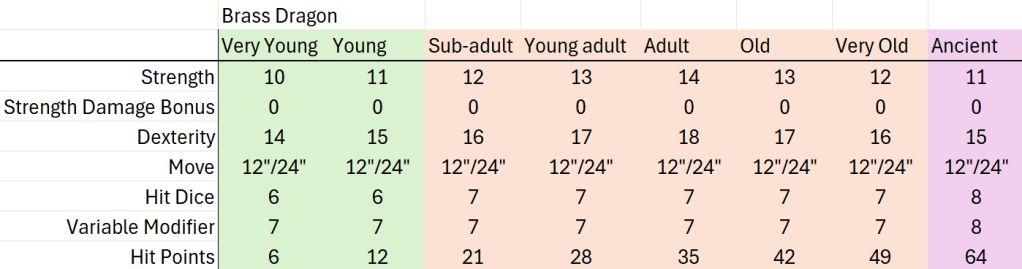

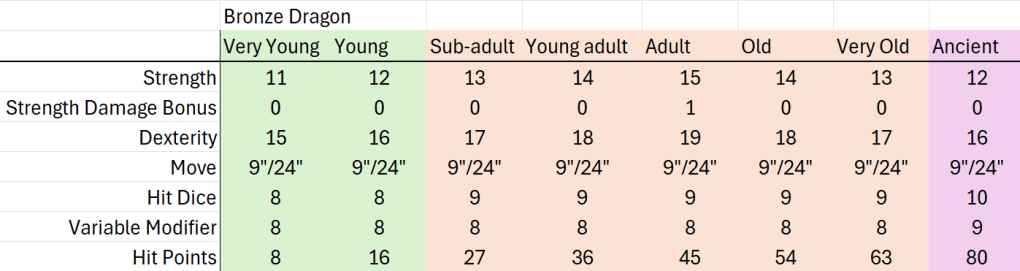

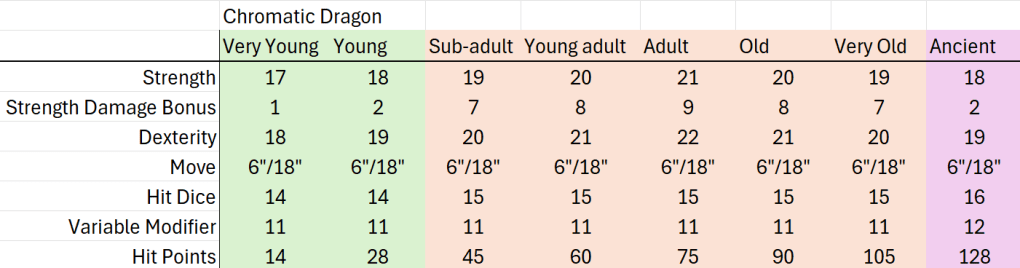

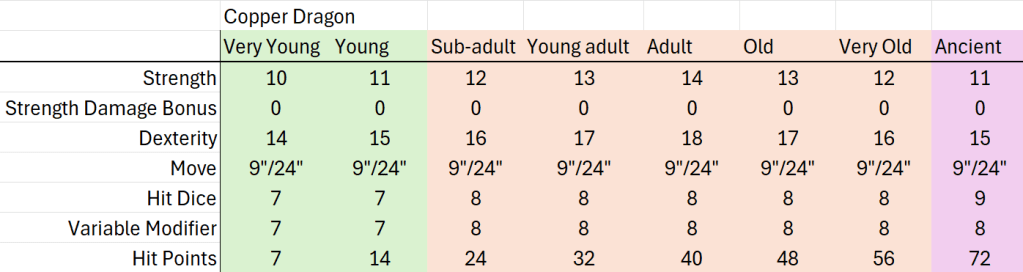

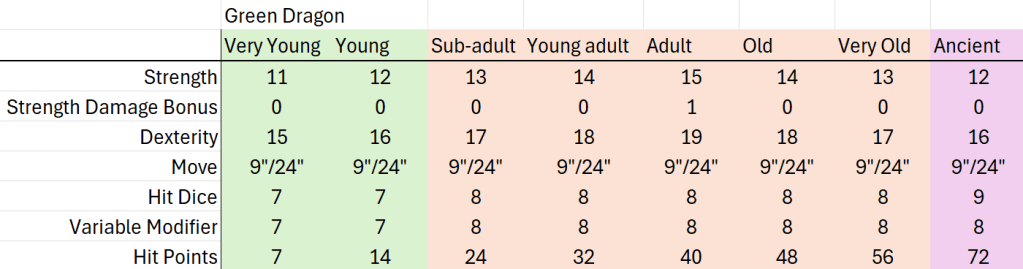

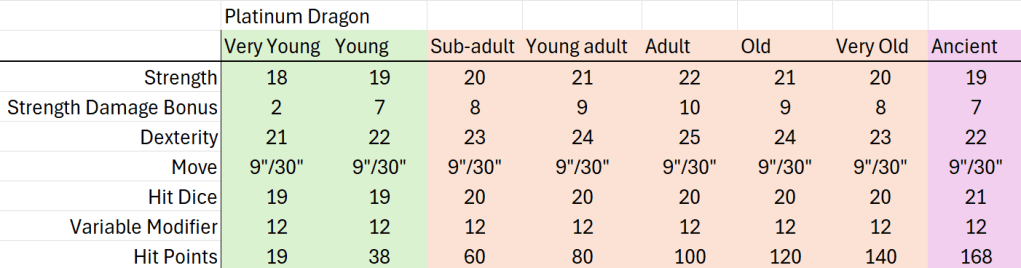

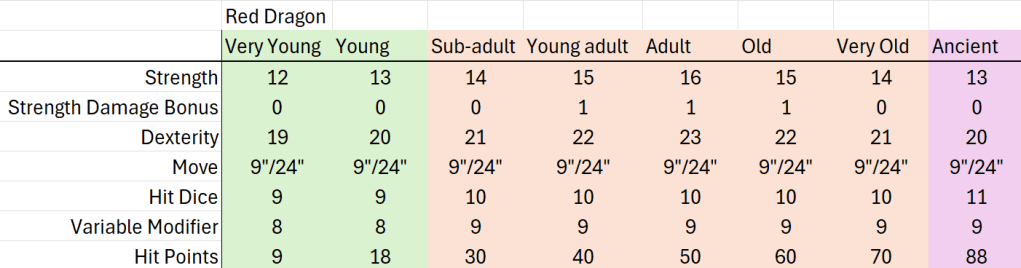

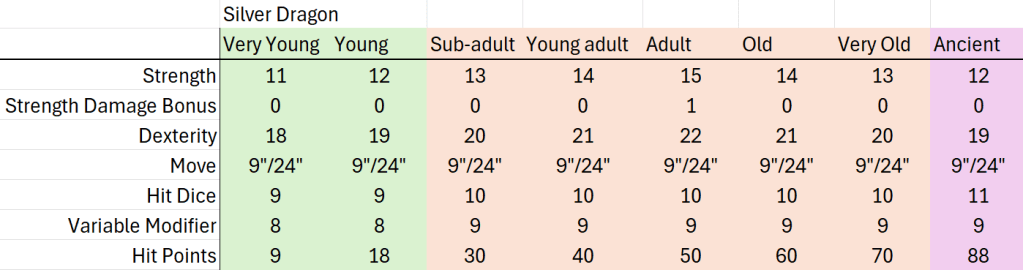

For horses, I based the strengths on the horse type carrying capacity listed in the Monster Manual. For dexterity, I based it on the horse AC of 7 (-1 AC for hide and the other -2 for dexterity). Again, one’s mileage may vary, but at least it’s a basis. Yet, for dragons, I have no idea of their carrying capacity or the basis for the armor class. In any case, for both horses and dragons, the listed strength and dexterity is for the purpose of unarmed combat only. Strength and dexterity effects on attack chances and melee damage are ignored because those are all subsumed in the monster listed hit dice and damage. There are damages listed in the unarmed combat results that are based on strength damage bonus, so I have listed that here. Upshot is I’ve based the strengths and dexterity for dragons more subjectively than for horses, including variety and fun.

From reviewing the tables, you can see I chose to favor dexterity over strength, for while full-grown dragons can be quite strong, I think dragons are more known for their sinuous snake-like abilities. I also had their strength and dexterity increase with growth and decline with old age. While an ancient dragon may be at their maximum hit points, they are behind their physical peak. For the singular ancient chromatic and platinum dragons, I cast backwards to assume their younger hit dice and physical abilities. While these

While there are certainly things to quibble about with my approaches here, and others might well make different assumptions as to weight and abilities, I think this set of characteristics for the dragons at their various ages will provide an interesting variety (96!) of dragons of various power and ability while also being consistent with older traditions which do not depict all dragons as the largest and strongest of beings. Dragons are fierce and not to be taken lightly, but many might well be overborn by a knight on horseback.

Leave a reply to Dragon Jousting Additional Information – Fluid — Druid Cancel reply