One of the great things about Hal Foster’s seminal Prince Valiant is that from very early on, Foster demonstrates how medieval combat was inextricably entwined with wrestling. The sequence below is one of the earliest examples, Val is losing versus the quarterstaff and resorts to grappling. It’s an early example, but the strip is full of wrestling. So should AD&D.

The best known mechanic in role playing games is the d20 system. There are various versions, but all feature a to-hit number that is determined by one’s armor class (perhaps modified by dexterity and magic) and the attacker’s level; if the target to-hit number is rolled or exceeded on a twenty-sided die, then the target has been hit. If hit succeeds, then damage in hit-points lost is rolled based on the weapon type. The two key parameters influencing success is type of armor and the ability (level) of the attacker.

One can see from the attack matrices, that first level fighters and clerics both start at first level with the same attack ability. Similarly, thieves and magic users also start with the same attack abilities, though theirs are both equal to the 0-level man, so worse than both the cleric and the fighter. The fighter has more increments of advancement than the cleric, as does the thief over the magic user. Note: that these increments are not quite the same as speed of advancement, as the class specific experience point tables set that rate. All things being equal, it should come as no surprise that, over time, generally a fighter will fight better than a cleric and thief better than a magic user.

For unarmed combat, the rules are much different. There are three types of unarmed combat, pummeling, grappling, and overbearing. All three follow the same basic procedure, though the parameters that affect success vary between them. The general approach is this, 1) determine a percentage chance of success, 2) if successful, roll for the level of success.

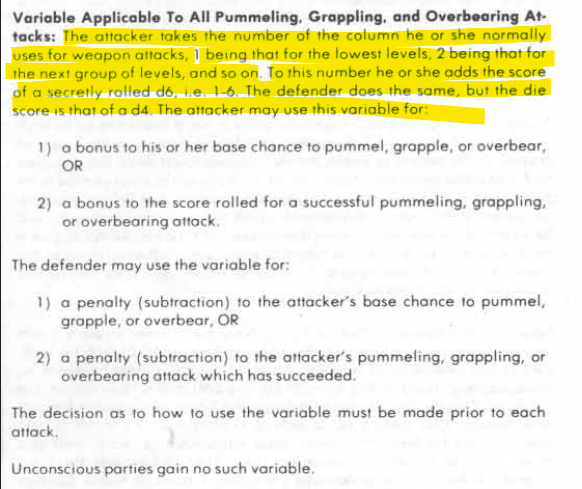

The other common element between all three types of unarmed is the variable die.

One important observation is that for all the unarmed combat types, the only place level of character comes into it is in this variable die — and that only based on the column one attacks on in the matrices. Well, there are also the number of hit points a character has which are affected by level, but that is important, but that is of secondary concern. Plus, the variable die only affects either the chances of success or the level of success, never both.

To see how this affects things, let’s take a look at an attack by a fighter. The attack die is 1 – 6 plus the column the fighter uses based on his level. So, for a first level fighter, one can see that fighters have a small advantage based on their class. A level one fighter gets a +2 to his variable roll because on the fighter attack table, level one appears on the second column. All other first level class types only start with a +1 because all other classes begin on the first column of their matrix. This is a true advantage, but a small one considering percentage dice are being rolled.

Now let’s look at a tenth level fighter. In normal melee, to hit an unarmored opponent (AC10) a first level fighter needs a ten or better to hit. A tenth level fighter needs a two or better to hit. So a 55 percent chance to hit raises to a 95 percent chance to hit at tenth level. A 73% improvement (95/55) However, for unarmed combat, discounting other factors (which do not change with level), the best a fighter can improve his unarmed combat is by +10%, really +8% since the fighter already starts at +2%. The other classes have it worse. Magic users a max of +5%, thieves +6%, and clerics +7%.

Note also, that race plays into this as well because of the level caps by class for the various races. Gnome and Halfling fighters are limited to a maximum of +4%. Elves and half-elf fighters to a max of +5%, and dwarves and-half-orcs to +6%. For thieves, half-orcs are limited to +2% while all other raves to maximum +6%. So a gnome or elf thief has a greater potential at unarmed combat than the gnome or elf fighter.

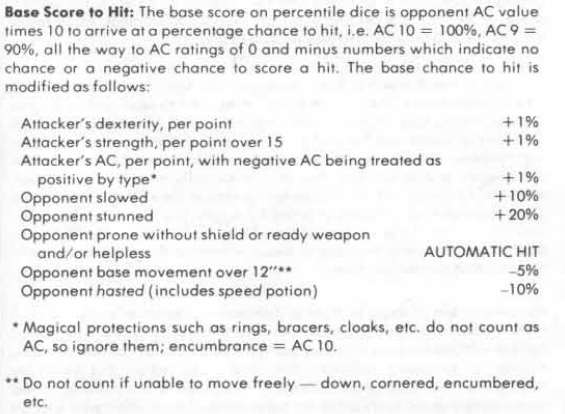

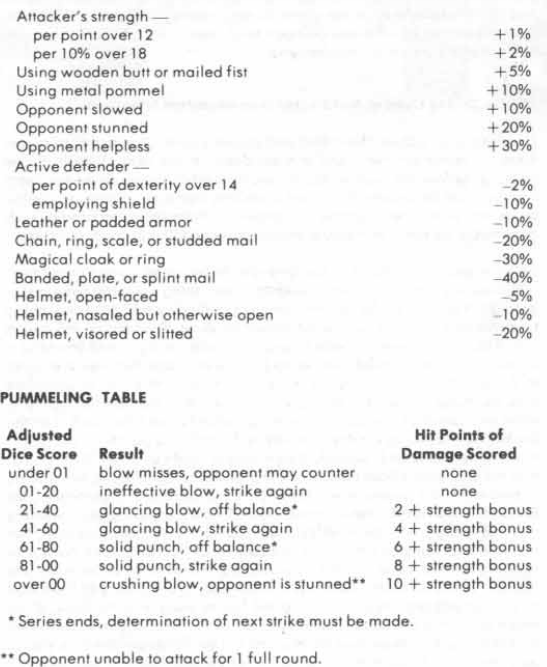

I’m not going to review in detail each of the three types of unarmed combat, but let’s just use pummeling as an example.

Base score to hit is the sum of one’s Dexterity, strength over 15, and armor class. Given ability stats range from three to eighteen with an eleven average, one can see that for the average person Dexterity is the most important influence on a successful punch. For two unarmored characters with strength and dexterity of eleven, they each will have a base chance to hit of 11+0+10=21 percent chance. Taken together, we’d expect one success between the two of them, about once every three rounds. These characters are not fighters, but zero-level NPCs. So for the variable, they will have on average +5 on the attack (average d6 roll is 3.5+1 =4.5=5) and +4 on defense (average d4 roll is 2.4+1=3.5=4). There are a number of possible scenarios to consider with the variable.

If both characters apply their variable to the attack, the attack base chance becomes 21+5-4=22. In that case, the attacker’s success is only marginally affected. But, should the attacker apply his variable to the effect roll (in the hope of a successful attack) and the defender continues defending the base change, the odds change to 21-4=17 — this is a significant reduction in his chance of success. If the attacker maintains apply his variable to the attack and the defender decides to use his to reduce the effect, the base chance becomes 21+5 =26%. But what about the effect?

It’s east to see that effect is greatly influenced by strength, especially exceptional strength (which only fighters can have). Effect is also increased by having a variety of hard things to strike with, but also mitigated quite a lot by armor. But dexterity is also a mitigation. And, for pummeling, strength and dexterity are at odds with one another. On attack base chance, dexterity is more important than strength, while for effect strength is more important than dexterity.

So, for our two average Joes pummeling each other, neither their strength, nor their dexterity (both being eleven) affect the outcome of the effect roll. For this example, only the variable matters. Again, there are a few scenarios. If the attacker chooses to place his variable on the effect then he get an average of +5. If the defender chooses to defend this, it drops to a +1. If the attacker has used his variable on the base chance roll, but the defender applies their defense to the effect roll then 0-4=-4. This doesn’t sound great. But note that this changes a one percent chance of creating both a miss but also gaining a counter, to a five percent chance.

The big thing here to understand is that while the variable can significantly change the odds in terms of percentages, the greater influence on both the base chance rolls and the effect rolls are both the roll itself being a percentage and a variety of constant factors that don’t change much (or at all) as a character rises in level. The most dexterity can change effect is eight percent while just striking with a pommel gives a ten percent change, while wearing plate mail and a visored helmet gives a 60 percent change. Even having 18/00 strength only shifts the roll 26% chance. I suspect, but am not sure, that the best use of the variable die is to influence the attack base chance.

Now, a quick look at best case pummelling. We have a fighter of level seventeen with Dexterity of eighteen and strength of 18/00. Best case of unarmored attack is 18+3+10 = 31. So thirty-one percent chance is the best anyone can do unless the opponent is slowed or stunned. Well, except if our beast fighter adds his variable, which would be at best +16 for a total 47% base chance to pummel. Now, let’s look at this beast going against our 0-level Joe Shmoe wearing plate, great helm, and shield — 26-40-20-10=-44. With an average die roll of 55, this gets reduced to 11, which is totally ineffective. Now, this beast fighter is going to win, because he gets to strike again, and this can just keep going until he eventually rolls above 65 and the damage (with his strength bonus) will take down a 0-level NPC. Yet, there is no arguing that the NPC has much better odds in this encounter than if the 17th level fighter had a weapon which (given his strength bonuses) would automatically hit.

While the parameters change between pummelling, grappling, and overbearing, the overall effect is the same, while the individual variable is not insignificant, often other factors have a greater bearing on success than level of the character.

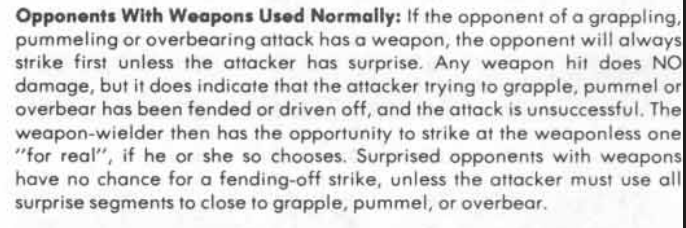

The upshot of this is that when faced with a greater level opponent, it may well be better odds for the lesser level to choose unarmed combat. But, let’s not forget the fending rule. And, an opponent with a weapon does get a chance to fend off the unarmed combat attack by using his weapon, unless he is surprised. So, those trying to capture a high level opponent for ransom are well advised to attempt to surprise them.

In any case, it’s obvious that the unarmed combat systems in AD&D really are a sea change from the normal combat procedures. This has upsides and downsides, I don’t know why this particular choice was made, but it can be refreshing when a character chooses to play a whole other game mechanic.

Leave a comment