Jeffro’s been talking about convergence for a long time. Bdubs too. They contrast diffusion with convergence. As I understand the thesis, his point is the great moments of gaming occur during periods of conversion. Multiple threads of events intersect and from the intersection amazing things happen. It’s exciting. Stuff goes down. Things explode. And everyone knows blowing things up is fun. The question then, in role-playing games, how to maximize the convergences?

But before we get to that, we need to look at diffusion. Jeffro quite explicitly states “diffusion and convergence is the name of the game”. And, he’s right. Things cannot converge unless they are first separated, that is (diffused).

But what is diffusion? It’s the natural tendency for things to move apart. Things in motion generally separate and move far away from one another to the point where they no longer interact at all. Everyone with a group of “friends” probably saw this during the covid era so should be able to intuitively understand the concept. But before covid, a more common model of thinking about diffusion was with the behavior of gases. The molecules of a gas released into a vacuum will diffuse extremely rapidly until there is little to no interaction between molecules. In terms of role-playing games, the molecules are the PCs or factions run by the players. Released into a vacuum, players will run in all directions and interact not at all. There will be no agreement on what the game even is. No common rules, no common genre. This is what rule zero gets you.

The most common method of containing a gas to limit diffusion and increase interactions is to confine the gas with a structure (a box or cylinder or sphere). Whatever the shape, you need a structure. Structure in the case of role-playing games, is the rules. And, genre but, really, genre and rules are the same thing. Genre defines what rules are adopted. One does not adopt rules for things outside a genre. Note here that the game world is defined by the rules and thus included within the rules. PCs will bounce around within the rules, interact with one another, and in aggregate will make a path unique to that character.

If the rules (box) is too big then players will not interact. They still will have unique paths, but they miss each other, and convergence does not happen. One can have an interesting game playing parallel solitaire (see many Eurogames). But, really, for a role-playing game parallel solitaire is suboptimal and less interesting.

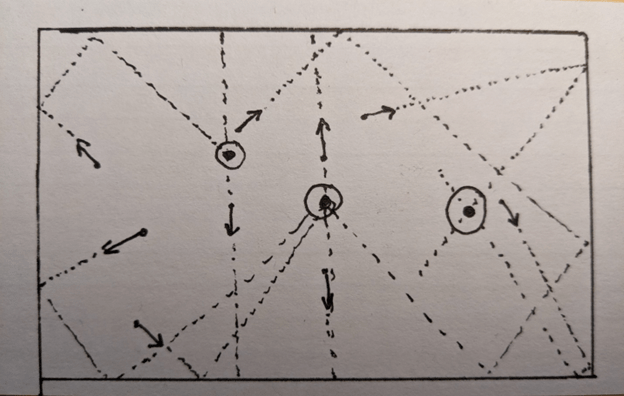

Using our gas model, each PC starts out with a vector of movement. This vector is defined by class abilities, character attributes and abilities, and idiosyncratic play defined goal developed in conjunction with class and character attributes. The are released into the game world (box as defined by the rules) to try things and interact with one another.

In my cartoon example here, you can see each PC with an initial vector, they bounce around until interactions occur (circled). The interactions are of various scales. Most interactions may be just two characters interacting, but at some point, there is a convergence. See there in the center, five of the nine PCs have converged into a big interaction and it is there exciting things happen. Who knows what might happen? Not all characters may survive. The surviving ones will have new unique vectors. Some might even stick together and travel for a time together on a common path until a following convergence knocks them apart again. It’s all very exciting.

So how to ensure these convergences? Using the gas model, this is called increasing the pressure. There are a few ways.

- Make the box smaller. This confines the PCs together and forces them to interact. We can see this in Jeffro’s Traveller game where he has imposed a single planet environment rather than a subsector. Or, you can see it in the old TSR Gangbusters game which primarily focuses on a single city environment. And, many others.

- Add more gas to the box. More players equals more potential interactions. We saw this with the first Brovenloft game. There were a ton of players and things went wild. In fact, with Brovenloft we saw both strategies in play – confined environment and many players.

- Heat up the box. This is taking putting outside energy into the box to force the particles to move faster – faster movement means greater potential interactions. This can take several forms. It might mean time pressure (with 1:1 time you want to get out of the dungeon before end of session to avoid being trapped in the dungeon. People get in gear when they know session end is approaching). Or, it can mean the Referee bullying people into interaction – pokes stick c’mon anthill do something. Arguably the latter is sub-optimal but opinions vary. It may well be necessary to motivate the players from outside the game but, one does wonder whether if the game presented does not motivate interaction, is it a good game (this is a sign the game needs fixing)?

There are two more ways to increase interactions in this gas/chemical model.

- Add a catalyst. In chemical reactions a catalyst is something that enables a reaction to occur more easily without itself being part of the reaction. In role-playing terms this may be things like random encounters, magical artifacts that multiple PCs might covet, supernatural events that change the environment.

- Increase the surface area (and/or decrease particle size). This one is tricky, in chemistry greater surface area means more things to stick to. Smaller particles tend to have greater surface area per volume (or mass). In game terms this might mean more attributes means more potential interaction or attributes designed to encourage or increase way to interact. For example the attribute of strength allows interactions like lifts, hitting, carrying, breaking things while charisma allows one to gather groups of NPCs who themselves will interact with things. This would probably be more as part of the initial game design but with play testing it might suggest means of changing the characters or rules to increase interactions.

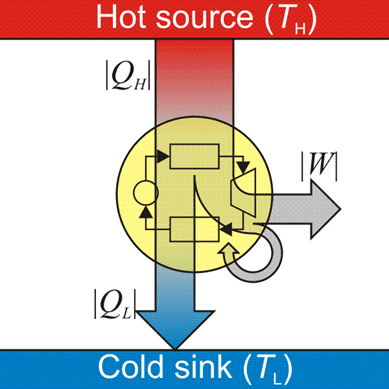

Now smart people are probably way ahead of me at this point. What comes out of models of gas diffusion is models of heat engines. For a long running game, you want a game that is a heat engine. One can confine a game until everything interacts and explodes.Or you can heat up a game until everything interacts and explodes. Or, you can pump more players into a game until they all interact and explode. Great you got explosions. But then everything flies apart and is diffuse again. It may be you never are able to bring those players together again. The explosions are exciting but a true game must then converge again. Put simply, a heat engine extracts work (fun) from a substance (players) by bringing a hot source (convergences) to a colder state (cold sink). Then it heats up the substance once again and repeats the process. Games fail when they 1) never heat up; or, 2) reach a cold state and fail to reheat (the famous RPG six session campaign).

One classic heat engine is the Otto Cycle. This is the cycle used by all spark ignited internal combustion engines. The Otto Cycle as applied to role-playing games includes:

- Air is drawn into a cylinder at constant pressure (PCs are placed in game with specific setting and rules)

- A piston compresses the air within the cylinder (This is game mechanic processes random encounters, etc that put pressure on the players)

- A constant volume heat transfer occurs – that is fuel is injected and an outside spark (or catalyst) heats up the gases (the players learn of a macguffin they might covet or some other mystery, or goal to achieve).

- Adiabatic expansion occurs. This is the extraction of power. This is the explosion driving everything apart. It’s exciting. In game terms this is when action goes down, PCs die, PCs survive, PCs get thrown into new trajectories.

- The cycle completes, heat is rejected from the engine while the cylinder is now again at maximum volume (PCs reap their rewards, gain their XP, do their training, are in time-jail, etc.).

- The heated air is released into the environment in preparation for drawing new air in at step on. In game terms this is dead PCs/NPCs abandoned, new characters are rolled, new random encounters are rolled, etc.

Note how this cycle can and does use all the mechanisms of increasing interactions.

Now there is another popular cycle, the diesel cycle, that is worth considering. The diesel cycle is the same as the Otto cycle with one difference. In step 3, no outside spark is required. The nature of the fuel/air mixture requires no outside spark to ignite. The Otto cycle, when working properly can continue indefinitely. The air/fuel mixture self-ignites and the cycle continues until interrupted. Arguably, the diesel cycle is preferable over the Otto cycles in a lot ways. A great game requires no outside spark to perpetuate itself.

But the model I’ve present in describing these cycles is wrong. The PCs are not the air, they are the fuel. It is the fuel that interacts with the air to create combustion. The players are the fuel. So, the Otto Cycle is not what we want. We don’t want the players injected just at the height of pressure. Because in those cases all the players are experiencing is endless explosions and go straight to diffusion. Or PCs are both the air and the fuel at different times. In any case, we want the players to experience the full range of the cycle. The compression stage is full of building excitement, the ignition stage is very exciting, and the cooling stage is the reaping of the rewards followed by preparation for a new compression stage. Each of the stages must happen for the engine to work.

Quite a lot more could be said using this model. Different cycles (why Stirling cycles might not be a great model for a game). Different means of adding energy to a cycle (fission/fusion). Ways of dealing with the inefficiencies of the cycles.

There is, of course, an element left out here. Players are not gases. They do not follow random paths. Players are intelligent. They follow their own ends to seek out or avoid interaction. It’s a rational tactic to try to avoid the dangers of the explosion while simultaneously partaking in the heat and reaping a reward. To a degree this is fine, not every atom that heats up in an engine is part of the reaction. But, a game has many fewer particles than an engine and it doesn’t take many wallflowers before no reaction occurs. One can try to force a reaction as a referee – get off the bench and get in the game! But ideally, the game itself is compelling enough that this is minimized. Part of ensuring this is to have players who know what the game is – that is they know the rules and thereby know the setting and know the genre and know then the sorts of things that may be expected of them to create reactions.

A good diesel engine only rarely needs to use the glow-plug.

Leave a comment