Mr. Wargaming has been exploring Boot Hill. And, he’s got my juices flowing thinking about role playing in a Western context. He’s been emphasizing that the strength of Boot Hill is its tight focus on combat rules. All the social interactions need no rules. The other player is sitting right there in front of you. You don’t need rules to ask, “You gonna pull those guns, or whistle dixie?” But, the combat rules in Boot Hill are deadly. The best strategy is to avoid combat. So, your social skills better be at high level, or be prepared to be pushed around by players more willing to take chances. In other words, Boot Hill follows the Braunstein style of play in order to run it as a campaign. This is similar to the other TSR game Gang Busters. Now, Gang Busters has a bit more than just combat rules, but it nonetheless follows a similar approach. What I want to do here is talk about another Western role playing game that takes an entirely different approach to the campaign, Gunslinger.

I’ve written about Gunslinger before, and some of this will be a regurgitation of that. But, also, my earlier discussion was on a different blog that has now been taken down. So, it’s worth getting something up on the subject here.

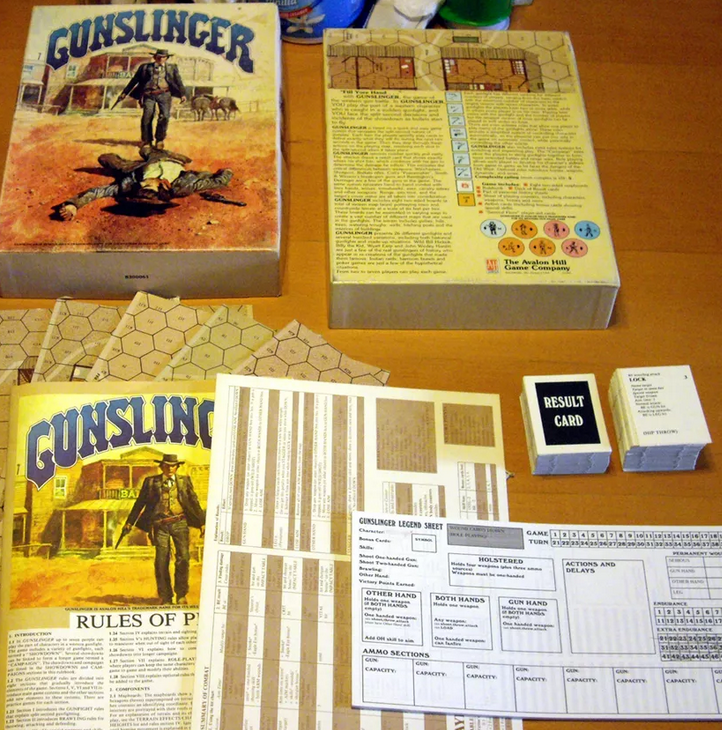

Gunslinger was published in 1982 by Avalon Hill. Avalon Hill is primarily known as a hex and chit board game publisher, and in most ways that is what Gunslinger is, a hex and chit board game of wild west skirmishes.

Without going into the details, the game primarily is a card-driven western shootout game. It’s a pretty innovative system, but being card driven, the game is component intensive, making it more difficult to republish than a typical role playing game. This makes finding old complete copies both somewhat difficult and expensive. I don’t expect any Gunslinger revival any time soon. As an aside, I sold my original copy on eBay, then years later decided I would like to obtain a copy. I scoured the internet found one, ordered it. When it arrived, I discovered it was the exact set I’d sold years before. I could tell by the way I’d organized the original card decks and pieces in the set. What are the odds of that? Maybe better than one might expect given the game’s marginal popularity. Enough of that. What I want to talk about here is not the combat system but the campaign game.

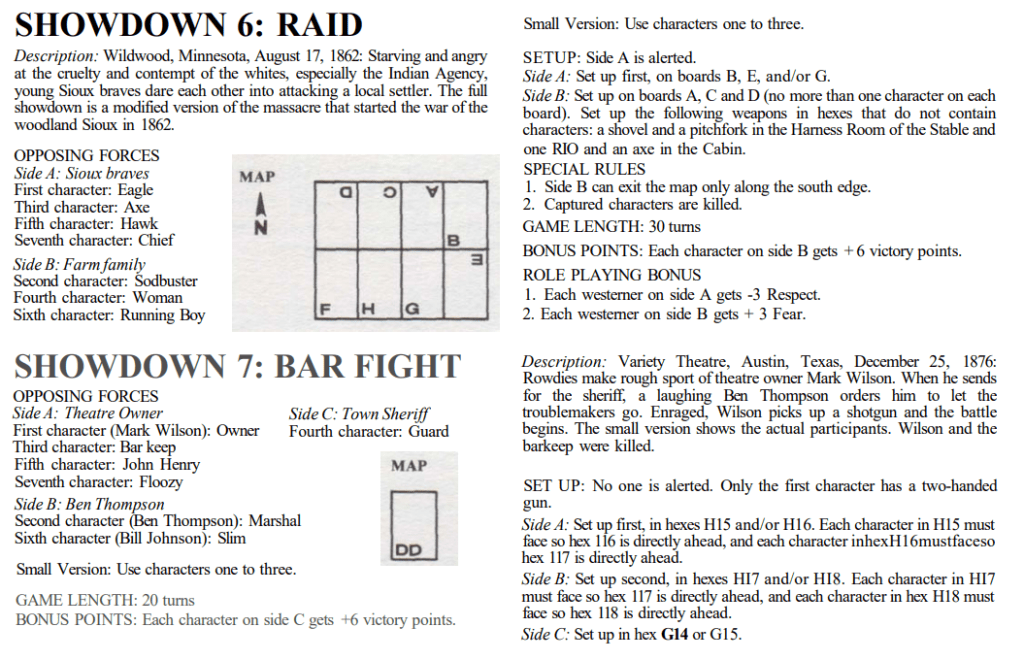

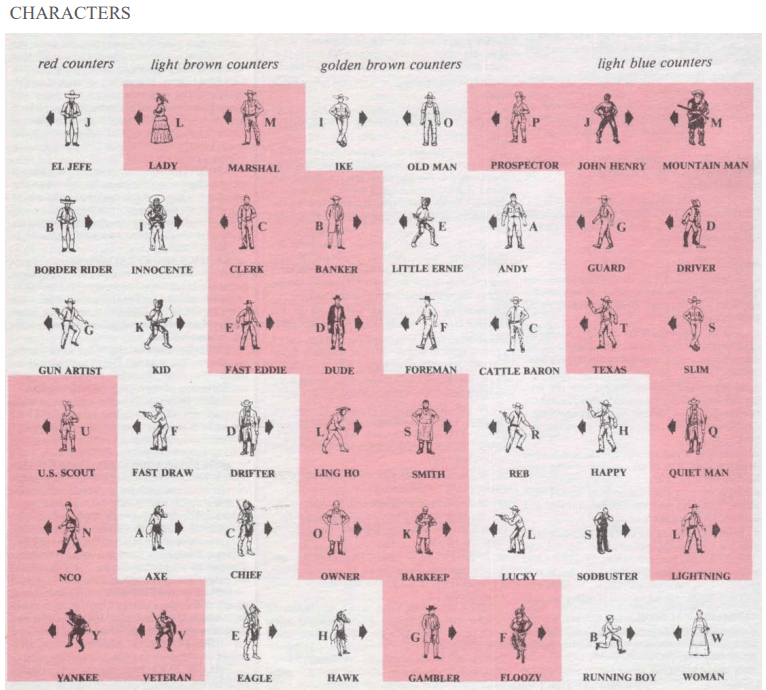

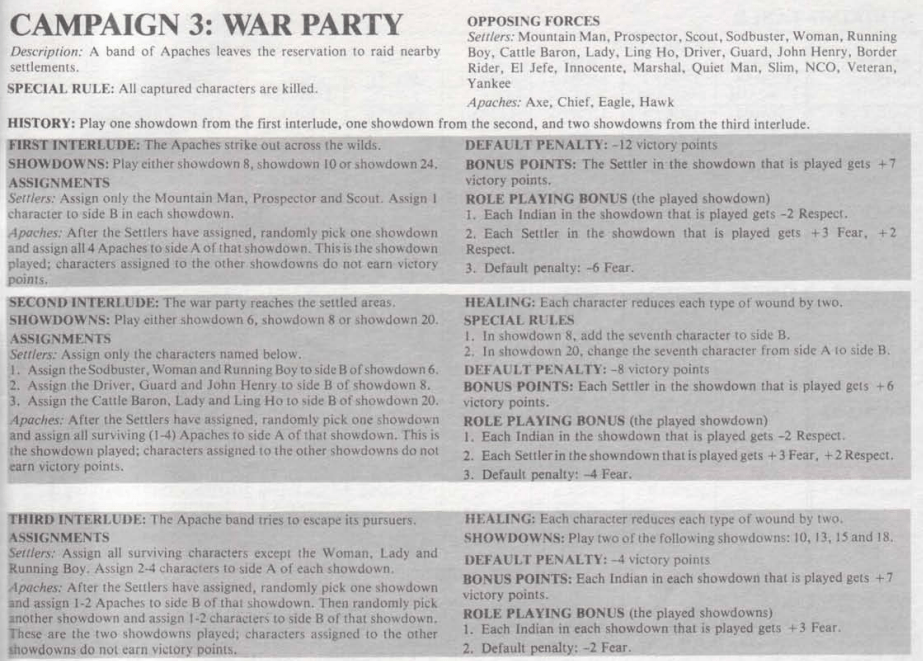

First, some discussion of terminology. Gunslinger has twenty-six standard scenarios called Showdowns. Showdowns define the forces present, board layouts, set up, special rules, game length, points, and “role playing bonus”. The Showdowns cover a fairly comprehensive list of typical wild west combat scenarios. Showdowns use Stock Characters that are defined in the game, you might think of them as archetypes or character classes.

Then there are “campaigns”. Campaigns are designed sets of Showdowns presented in a particular order with defined interludes between Showdowns.

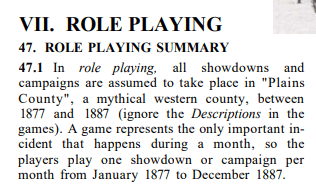

Then there is what is called “Role Playing”. Role Playing, as defined by Gunslinger is, in essence, an extended campaign.

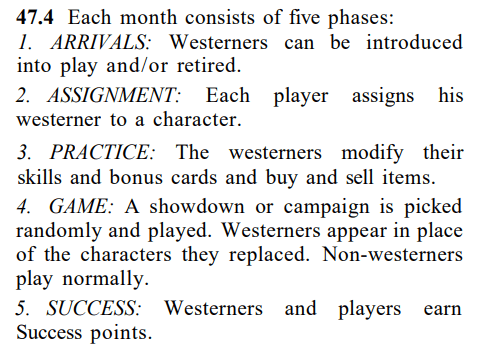

Role Playing uses monthly turns, themselves broken into five phases.

Westerners are characters. A player can/will build up a stable of Westerners as the Role Playing element progresses. Each Westerner is fit into one of the stock archetypes used in the Showdowns. If a player has a Westerner that fits that month’s Showdown, then, it can fill that role in that Showdown. Otherwise, the player plays one of the other roles (ie NPCs). In essence, players, carry out one Showdown per month, the results of these showdowns define whether their Westerners live or die, how they prosper, and whether they are forced to retire. Characters can also be retired voluntarily and miss a year of game time, to then be brought out of retirement. Players and Westerners earn Success points based on the outcome of the Showdowns. During the ten-year period of the Role Playing element, one-hundred-and-twenty Showdowns occur. Players accumulate points based on the results of the Showdowns. At the end of the ten-year period (December 1887), each player averages their Success from their stable of Westerners to determine the winner.

In between Showdowns, characters can use earned money to buy better weapons and ammo. They can also practice improving skills.

How are the Showdowns determined? Semi-randomly. Players secretly vote on a Showdown or Campaign type, then which one is drawn from a hat (presumably a ten gallon one).

The rules don’t say this, but presumably there is a canvassing portion of the game where players have a chance to advocate for the scenario they want. For example, a monthly Showdown is more safe than a campaign because it is one Showdown whereas a month-long campaign is multiple showdowns. Advocating for one or another might bear advantages depending on which Westerner the player has available that month.

Now, this all seems rather rigid and, arguably, over-defined as compared to a typical role playing game. But, the Showdowns can be modified or also created uniquely based on circumstances. What those circumstances are, I can’t say. But, I expect that is where apophenia comes in.

Apophenia is seeing patterns in chaos. Or, making sense of chaos. I expect, as the months progress and after a few Showdowns occur, players will start to make stories out of the results for their Westerners. Then they will start having opinions of which Showdown follows thematically for their Westerners. At that point, they might start saying, of yeah, Showdown 16 Bushwacking (or whatever) should be next, but it should be modified in ways, X, Y, Z because we have characters A, B, C available. Then collaboration takes off.

Or, at least, that’s my speculation. I’ve never played the Role Playing aspect of the game. But, that is my guess. It’s much more defined that a typical Braunstein-like game. But, also, it provides the base tropes of the genre from which improvisation can occur. So, in a way, it is an anti-Braunstein, in that the structure is very rigid. Yet, it also has a flexibility that is built in which can result in a meta-Braunstein like result. Players are aware of what’s going on with all the characters, what the range of possibility in scenarios are available, then use the knowledge to influence the next step in the game.

In any case, it’s a different approach, I’ve not seen anywhere else. The closest I get is the less defined Gang Busters weekly turn. It’s worth a look at when assessing the full scope of possibilities in role playing games.

Leave a comment