AD&D is pretty famous for having a fairly extensive weapons list, including in particular quite a lot of different types of pole arm. However, a couple of recent videos (here and here) by the esteemable Matt Easton of the YouTube channel Scholagladiatoria recently made some points that reminded me of things I’ve noticed are missing from the AD&D equipment list.

The first weapon Mr. Easton discusses is the Dane Axe, famous for its use by the Britons in their famous loss at the Battle of Hastings. Mr. Easton speculates pretty convincingly that the Dane Axe may well have been a specialized weapon for fighting horses. And, he addresses the first question I had when I heard that, “Didn’t they already have the perfectly good horse-fighting weapon, the spear?” He points out that while, yes, they did have spears, the spears and tactics used in this period may not have been as effective as one might hope against cavalry charges.

The general tactic being the shield-wall, where men with shield and spear interlock their shields to form a united front against all comers. And, there on the Bayeux Tapestry they are.

We see a shield wall with a man out front with the Dane Axe. The man is not in a formation of men with Dane Axes. The thought is that the axe men might well be there to chop the lead horse, which then would like dominos disrupt the rest of the charging cavalry. There are a few other things to note. First, the spears born by those in the shield wall don’t look particularly long, nor are they set in the ground to receive a charging horse. Second, the charging cavalrymen, while well armored themselves, their horses are unarmored. Third, the horsemen themselves are not charging with couched lances. This is Hastings, which is pretty early in the history of the knightly charge with lances.

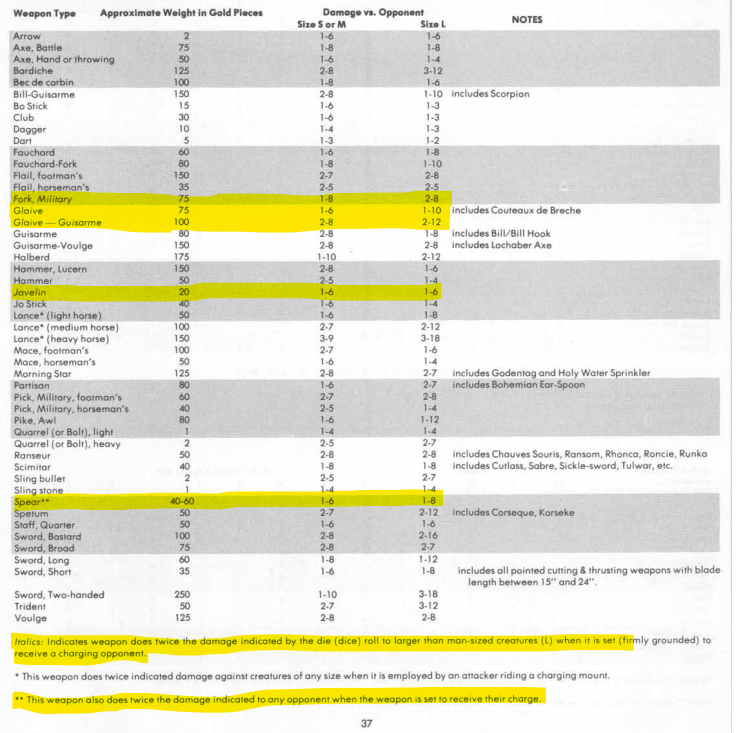

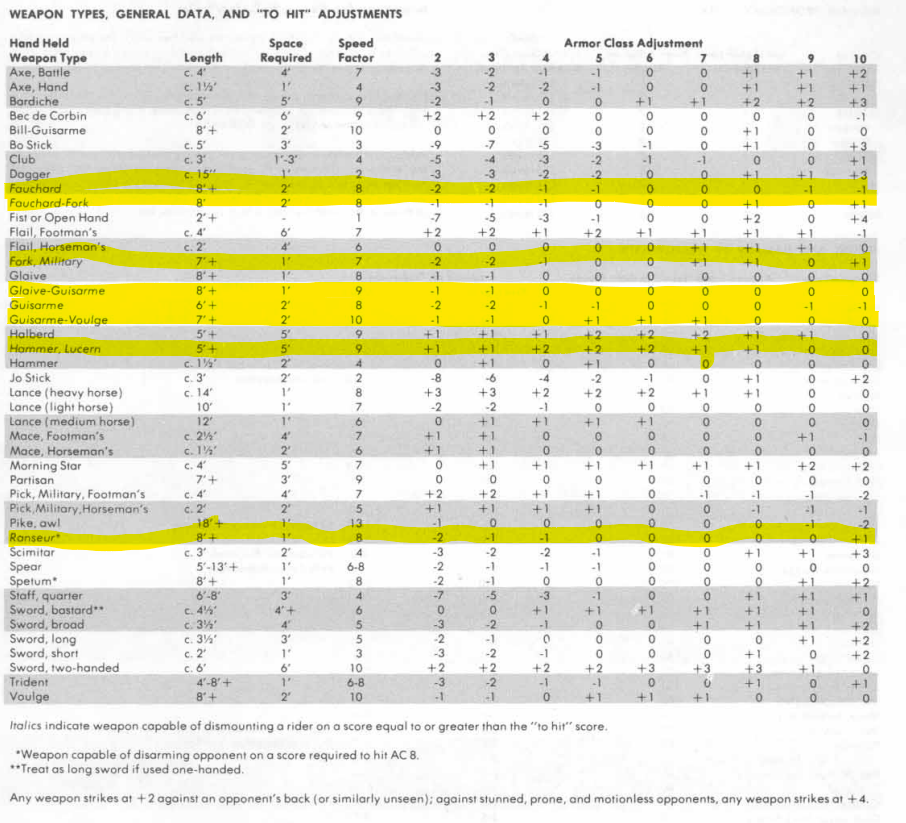

The spear in AD&D is a pretty robust and pretty optimized weapon. I’ve discussed this before here. The spear is cheap, can be packed into tight formations, and has the ability to be set against charges. There are several weapons that the game allows to be set against charges, the military fork, the glaive, the glaive-guisarme, even the javelin. But all these can only be set to do double damage against large opponents. So, really, primarily the large opponents will be horses. The spear has the unique ability to be set against all charges of whatever size.

There is another class of weapons in AD&D, while not specifically anti-horse, are anti-cavalry. These are weapons capable of dismounting a rider, the fauchard, fauchard-fork, military fork, glaive-guisarme, guisarme-voulge, and lucern hammer. Some of these have both the ability to do double damage to large creatures or to dismount a rider. Presumably, the wielder of the glaive-guisarme, for example, must choose to either set the weapon and attack the horse, or not set the weapon and try to dismount the rider. Or, this may be taken out of one’s hands should one lose the initiative and not have the opportunity to set the weapon for the charge.

It is notable the lances are not listed as weapons capable of dismounting a rider. This may be an oversight. Though, I have a sneaking suspicion that it is due to an expectation that lance versus lance attacks will be resolved using the Chainmail jousting matrix. More on jousting here. It is also notable that the spear is not listed as a weapon capable of dismounting an opponent.

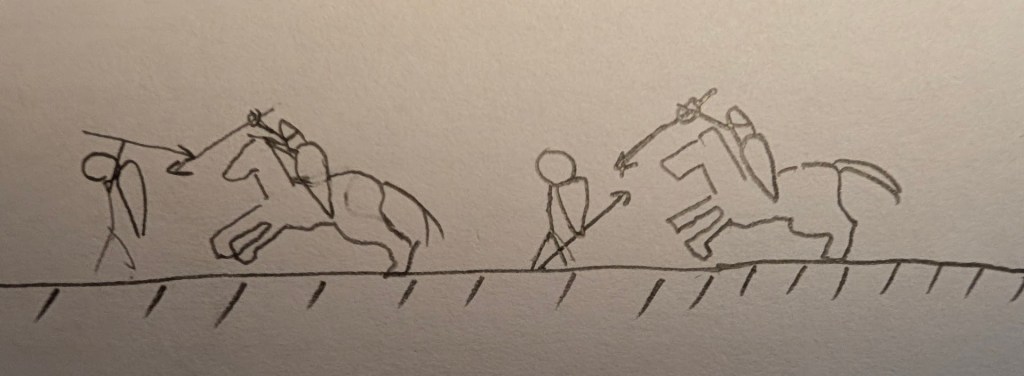

But back to the spear. The length of the spear shown in AD&D is 5′ to 13+’. Quite a variation in length. From the Bayeaux Tapestry, I take the spears of the Battle of Hastings to be on the short end. In geometry terms, If one has a short spear, and it’s butted into the ground, then the horseman that does not need to butt his spear, may well be able to reach the footman before the footman can reach the horse.

So, while the set spear may do double damage against the charge, the short-speared soldier might never get that chance. And, we do see, over the length of the medieval period and into the Renaissance, the length of spears extending until they become a whole other class of weapon — the pike. This may be the answer to something I’ve wondered about. If spears are so great against cavalry, how was there a three to four hundred year period where the cavalry charge was considered a major tactic when most soldiers were equipped with the horse-defeating spear? The answer being short spears are overrated, especially in eras where they were pretty short and lances got longer.

In AD&D terms, lances are 10′ (light), 12′(medium), and 14′ (heavy). Most spears will be shorter than the lance. So, the lance strikes first in the charge, except for the longest of spears. But at Hastings, they didn’t have long spears. The lances, too, don’t appear so long either, but even equal the lance likely strikes first. The long lance also has the advantage of the extra weight being carried by the horse, while the footman has to bear every pound of his spear. It’s a small difference, but I think a real one.

Now back to the Dane Axe. The Dane axe was a long weapon, four to six feet or so, and weighed up to a bit over four pounds more or less. It has a big blade with a 20-30 cm edge. But, it was a thin blade. As an axe, the Dane Axe was not particularly robust. It was made to hack flesh, but not really designed to break armor. The knights at Hastings were well armored. But the horses were not.

Now, it is reasonable to argue that AD&D includes a battleaxe listing and that should be sufficient to represent the Dane Axe. And, generally, sure, probably so. But battleaxe as listed doesn’t quite fit the use case of the Dane Axe. Damage against large creatures for the battleaxe is a mere 1-8 hit points. And, while the battleaxe does get some negative bonuses against the heavier armors, they are right in line with many weapons. My take is the battleaxe listed in the PHB is intended to represent a later medieval axe built more robustly, but without the same wicked thin edge of the Dane Axe.

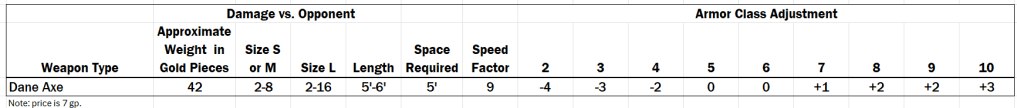

So, below is the Dane Axe for AD&D. It has significant bonuses when facing unarmored or lightly armored opponents, but faces considerable challenges against the heavily armored. Damage against large opponents is sufficient given an average roll to give a decent chance of taking out most horses, except for the heaviest of the heavy war horses.

The other weapon missing from the AD&D weapons list is the falchion.

Now, I’m not going to go all in on the falchion as I did with the Dane Axe. Suffice it to say, the falchion was a pretty common weapon throughout the 13th to 16th century, and yet is missing from the AD&D weapons listing. The falchion came in various forms, but the uniting feature of it was a largish chopping blade, that like the Dane Axe was thinner and sharper than one might expect from just looking at drawings. The falchion was something like a big whopping machete.

Why was the falchion popular in the late medieval period, given their poor showing against armor? Because there were a ton of soldiers who weren’t so heavily armored. The common soldier did not have the means of an armored knight. And, heck, even an armored knight, often dispensed with visors when on the field to aid in sight. Chopping the armored knight in the face was often near as effective as, well, chopping anyone in the face.

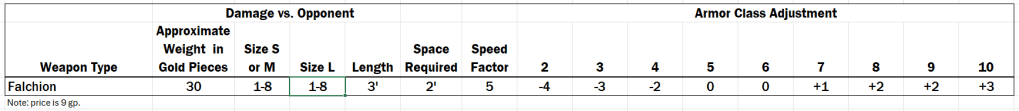

One can use the scimitar as a stand-in for a falchion. But, here is mine. I gave it the scimitars damage, a bit slower speed than a scimitar, and the same advantages/disadvantages against armor as the Dane Axe.

In summary, if one wants to add a little flavor to one’s game, here are the Dane Axe and the Falchion for AD&D. And, for those referees running games, one might start asking pointed questions as to the length of PCs spears, when adjudicating issues of weapon length. Those who take the longest of spears to get that first hit, should have problems maneuvering them in dungeons, and revolving doors.

Addendum:

This video provides background to a point I wanted to include but forgot.

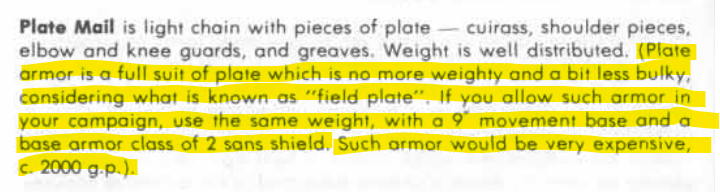

The armor discussed in the video is the “plate mail” that is included in AD&D. The only helmets included in AD&D are a small helm and great helm. No later types of helmet are discussed is AD&D (with one caveat). So this places AD&D around 1300 or so. Great helm use dropped off around 1340 as other helmets began to be developed (great bascinet).

Later period weapons listed in AD&D, the two-handed great sword, a few pole arms, arguably some forms of scimitar. So, it is understandable that the Dane Axe is not included in the weapons list. It is less understandable to not include the falchion, though it is somewhat early in the period that falchions were popularly in use. Early, but the falchion was still well established in 1300.

“Field Plate” sound more like the armor of a hundred years later, much like that used at the Battle of Agincourt. So, more or less, shifting things from around 1300 to around 1400. And, note that this is a referee optional choice to include it.

Leave a comment